|

Digital Security and Privacy for Human Rights Defenders |

|

1.1 Security and InsecurityComputers and the Internet are all about information seeking, storage and exchange. Hence, the topic of security in the digital realm relates to the security of information. We need to operate in a climate where our information is not stolen, damaged, compromised or restricted. The Internet, in theory, provides everyone with an equal opportunity to access and disseminate information. Yet, as many incidents have shown, this is not always the case. Governments and corporations realise the importance and value of controlling information flows, and of being able to decide when to restrict them. The security of information is further complicated by malicious individuals creating computer viruses and hacking into computer systems, often with no other motive than causing damage.Confusion is enhanced by the abundance of software, hardware and electronic devices designed to make the storage and exchange of information easier. An average computer today contains millions of lines of complex code and hundreds of components which could malfunction and damage the system at any time. Users have to immerse themselves in concepts and technology that seem to be far removed from the real world. The security of your computer falls first and foremost upon your shoulders and requires some comprehension of how its systems actually work. The race to reap profits from the Internet has resulted in the appearance of numerous financial services and agencies. You can now book a flight, buy a book, transfer money, play poker, do shopping and advertise on the Internet. We have increased our capacity for getting more things done more quickly, yet we have also created a myriad of new information flows, and with them – new concepts of insecurity we do not yet know how to deal with. Marketing companies are building profiles of users on the Internet hoping to turn your browsing experience into a constant shopping trip. Personal information, collected by governments and social agencies, is then sold to data mining companies, whose aim is to accumulate as much detail as possible about your private life and habits. This information is then used in surveys, product development or national security updates. Our email accounts are cluttered with useless and unsolicited messages, causing a huge disruption to our work, the Internet connectivity and computer reliance. It appears that chaos has come to rule our digital world. Nothing is certain and everything is possible. Most of us just want to get on with writing our document or sending an email, without considering the outcomes of insecurity. Unfortunately, this is not possible in the digital environment. To be a confident player in this new age of information highways and emerging technologies, you need to be fully aware of your potential and your weaknesses. You must have the knowledge and skills to survive and develop.

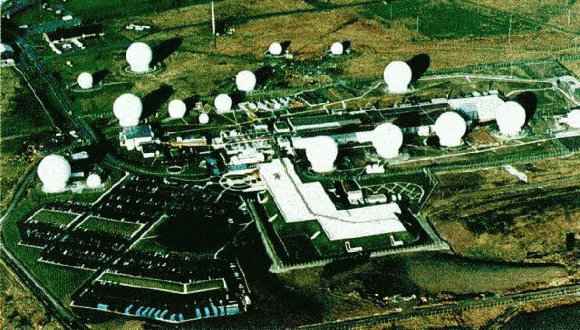

ECHELON intercept station at Menwith Hill, England.

Source: www.greaterthings.com In May 2001, the European Parliament’s Temporary Committee on the Echelon Interception System (established in July 2000) issued a report concluding that “the existence of a global system for intercepting communications . . . is no longer in doubt.” According to the committee, the Echelon system (reportedly run by the United States in cooperation with Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) was set up at the beginning of the Cold War for intelligence gathering and has developed into a network of intercept stations around the world. Its primary purpose, according to the report, is to intercept private and commercial communications, not military intelligence.1 The right to freedom of expression and information has also been attacked and suppressed on the Internet. The ability to access information from any Internet connection point on Earth, regardless of where this information is stored, has resulted in many governments – not ready or willing to provide this type of freedom to their citizens – scrambling to restrict such free access. Huge resources have been poured into developing country-specific filtering systems to block the Internet information, deemed inappropriate or damaging to the local country’s laws and ‘national morale’. In China, a system known as the “Great Firewall” routes all international connections through proxy servers at official gateways, where the Ministry for Public Security (MPS) officials identify individual users and content, define rights, and carefully monitor network traffic into and out of the country. At a 2001 security industry conference, the government of China announced an ambitious successor project known as “Golden Shield.” Rather than relying solely on a national Intranet, separated from the global Internet by a massive firewall, China will now build surveillance intelligence into the network, allowing it to “see,” “hear” and “think.” Content-filtration will shift from the national level to millions of digital information and communications devices in public places and people’s homes. The technology behind Golden Shield is incredibly complex and is based on research undertaken largely by Western technology firms, including Nortel Networks, Sun Microsystems, Cisco and others.2 These filters undermine our ability to take advantage of the Internet and to cross geographical boundaries in our quest for learning and communication. They are also in breach of several articles in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) guaranteeing every person rights to privacy and free expression. Significantly, these systems were developed only after the growth and potential of the Internet as the global information exchange was noticed. They were not part of the original idea behind the development of the Internet. Surveillance and monitoring techniques have passed from the hands of intelligence personnel to the hardware and software systems, operated by private companies and government agencies. Phone bugging and letter opening has been superseded by the technology that allows monitoring of everyone and everything at once. The popularity of the Internet and its integration into our daily life has made that possible. Previously, someone considered dangerous to national security was spied upon. Now, we are all under suspicion as a result of the surveillance and filtering systems our governments install on the Internet. The technology does not often differentiate between users as it waits for certain keywords to appear in our email and Internet searches, and when triggered, alerts surveillance teams or blocks our communications. In 1998, the Russian government passed a law stating that all Internet Service Providers (ISPs) must install a computer black box with a link back to the Russian Federal Security Services (FSB) to record all the Internet activity of their users. I have witnessed such Internet-based filtering repeatedly. In the days following the attacks on the New York Trade Centre, while working for a global computer company, I had an urge to explore the obscure world of religious fundamentalism. After browsing through certain extremists websites, I was approached by two of the company’s security guards who asked me why I was looking for that particular information. At first, I was dumbfounded – how did they find out? Then I asked the guards who gave them the right to question me. The next day, a company memo banned all staff from visiting websites that contradicted “the organisation’s ethics and policy’”. The debate about controlling the Internet and information flows for the purposes of countering terrorism is outside the boundaries of this manual. It has to be said, however, that such practices have reduced freedom of expression, association and privacy all over the world, in direct contravention of the UDHR. Governments have installed systems to monitor their citizens on the scale far beyond the measures to fight terrorism. Information on human rights, freedoms of the media, religion, sexual orientation, thought and political movements, to name just a few, has been made inaccessible to many. ...“The Uzbekistan government has reportedly ordered the country’s internet service providers (ISPs) to block the website www.neweurasia.net, which hosts a network of weblogs covering Central Asia and the Caucasus. The government’s decision to block all national access to www.neweurasia.net is believed to be the first censoring of a weblog in Central Asia...”3 ... “The Socialist Republic of Vietnam regulates access to the Internet by its citizens extensively, through both technical and legal means. According to the study by the OpenNet Initiative (ONI), the Vietnamese state attempts to stop citizens from accessing political and religious material deemed to be subversive along various axes. The technical sophistication, breadth, and effectiveness of Vietnam’s filtering are increasing with time, and are augmented by an ever-expanding set of legal regulations and prohibitions that govern on-line activity. Vietnam purports to prevent access to the Internet sites primarily to safeguard against obscene or sexually explicit content. However, the state’s actual motives are far more pragmatic: while it does not block any of the pornographic, it filters a significant fraction - in some cases, the great majority - of sites with politically or religiously sensitive material that could undermine Vietnam’s one-party system...”4 Encryption has become one of the last resorts of privacy on the Internet. It enables us to make our messages and communications unreadable to all but the intended party. A layer of encryption was even built into the Internet structure to allow for secure financial transactions (SSL). When this system began to be applied for securing other, non-financial, information, it was met with strong opposition in many countries. At first, the US government tried to ban all SSL encryption of the complexity higher than they could decrypt. In 2000, Britain, in her turn, introduced the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIP) which made no provisions for one’s right to encrypt information, but stated that a user must surrender his passwords when asked to do so by the investigative forces or face 6-month imprisonment. In 1998, the government of Singapore passed the Computer Misuse Act that allowed the country’s security services to intercept email messages, decrypt encoded messages and confiscate computers without a warrant in the course of investigations5. Some countries, like Turkmenistan have banned encryption altogether. A world-wide monitoring system, like ECHELON (or any other), will probably collect all encrypted emails for further inspection, simply because they were encrypted in the first place. Any attempt at privacy will therefore be seen as an intention to hide something. Specific threats faced by human rights defendersHuman rights defenders often become targets of surveillance and censorship in their own country. Their right to freedom of expression is often monitored, censored and repressed. Often they are facing heavy penalties for continuing their work. The digital world has been both a blessing and a curse for them. On the one hand, the speed of communications has brought them closer to their colleagues from around the world, and the news of human rights violations spreads around within minutes. People are being mobilised via the Internet, and many social campaigns have moved online. The negative aspect of the widespread use of computers and the Internet lies in over reliance on complex technology and the increased threat from targeted electronic surveillance and attacks. At the same time, the defenders in poorer countries who do not have computers and/or access to the Internet have found themselves left out of global focus and reach – another example of the imbalance caused by the digital divide.Over the years, HRDs have learnt to operate in their own environment and have developed mechanisms for their own protection and prevention of attacks. They know their countries’ legal systems, have networks of friends and take decisions based on everyday wisdom. Computers and Internet, however, constitute a whole new world to discover and understand. It is their lack of interest or capacity to learn about electronic security that has lead to numerous arrests, attacks and misunderstandings in the HR community. Electronic security and digital privacy should become not just an important area for comprehension and participation, but also a new battleground in the struggle for the worldwide adherence to the principles of the UDHR. Emails do not arrive at their destination, Internet connection is intermittent, computers are confiscated and viruses damage years of work. These problems are commonplace and familiar. Another common phenomenon is the increasing attention of those in power to online publishing. The authorities are actively searching through Internet news sites, blogs and forums – with swift retribution in cases when “undesired” material originating from a HRD is discovered. Take the case of Mohamed Abbou, who is serving a 3,5 year prison term in Tunisia for publishing online an article that compared Tunisian prisons to Abu Ghraib6. In China, 48 journalists are in prison because of their Internet-related activities7. Human rights defenders need to secure their work by learning about the technology and concepts of the computer and Internet operations. This will make them more effective in protecting themselves and in promoting the rights of those they try to defend.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7 |